Alastair Philip Wiper

Interview

The photographer and author of The Art of Impossible: The Bang & Olufsen Design Story tells us about his fascination with heavy industry, shooting CERN's Large Hadron Collider and scouring the B&O archives for product prototypes.

How did you become a photographer?

I come from a town called Guildford about 50 km south of London. After studying philosophy and politics at university in the UK, I travelled a bit. I met a Danish girl while working as a ski-bum in France – I followed her to Denmark and haven’t looked back since. That was in 2004. I broke up with the girl after a few years, found another Danish girl. And now I’ve got the kids, the house, the whole package. I was actually a cook when I first came here. But I became interested in graphic design, I taught myself some stuff and ended up working for designer and artist Henrik Vibskov. I worked for him for eight years, and during that time I picked up a camera and started playing. Before I knew it, I was the photographer as well as the graphic designer.

You photograph a lot of different subjects: industrial, scientific, and architectural projects. What do you find interesting about them?

I love going behind the scenes and seeing things that other people don’t get to see. I feel extremely lucky to be able to do that. I am particularly attracted to the industrial and scientific work, because here I get to explore the insane solutions that human beings come up with to solve problems. Like building huge infrastructures to provide cities with power or entire continents with pork. Or massive machines that can analyse the smallest particles in the universe to help us understand what life is all about. The architectural stuff I do tends to be a bit quirkier. But I still take the same approach towards the subject matter. I am not a conventional architecture photographer. I am more interested in finding the work of eccentric, half-forgotten architects who were doing things out of the box and showing their work in new ways. Like the work of Jacques Labro in Avoriaz or César Manrique in Lanzarote. A few years ago, I also started to write as I felt it gave my images some extra context. I want people get a feeling for what I experience when I visit these places, and add some information that I think makes the pictures more interesting.

How did you start out shooting these subjects?

About five years ago, I came across a couple of photographers who worked for “big industry” in the 1950s and 60s: Wolfgang Sievers and Maurice Broomfield. They photographed big oil refineries and manufacturing plants at a time when the companies that owned them were proud of them instead of ashamed, as they tend to be today.

I was totally amazed. It was like a lightbulb moment, where I knew that was what I wanted to photograph. So, I started researching like crazy and trying to talk my way in anywhere I could in order to build a portfolio. Over the past few years, a lot of my time has been spent learning how to get a hold of the right person and how to convince them to let me into their facility.

Do the subjects just land at your feet or do you have to go out of your way to gain access?

These days I'm lucky enough to get commercial and editorial work that I find very interesting. But I still spend a lot of time researching places to visit for personal projects. It can take a lot of work to get into some places. Sometimes I reach a wall, where I get the wrong person who just doesn’t understand, what I am trying to do. Or why it could also be an interesting project for them. But like I said, I have gotten quite good at it over the years.

One of the easiest places I got access to, was actually the place I thought would be the hardest: the Large Hadron Collider at CERN in Switzerland. When I was just starting, I planned a trip there, just to take their regular tourist visit. But I also sent an email to the press office asking if there was anything, I could see that the other tourists don’t get to see. To my surprise they offered me a private guided tour. That afternoon, my guide was an engineer who had worked on the LHC for about 30 years. We stayed in contact, and I’ve been back again twice. The last time CERN commissioned me to photograph their facilities, which was pretty much a dream job for me.

What’s your favourite project?

One that really stands out was photographing the building of the Maersk Triple E in South Korea, the biggest container ship in the world, for Wired Magazine. That was just epic, seeing these huge blocks of ship being lifted around and put together like bits of Lego. I also love the series I did about the Danish Crown slaughterhouse in Horsens, one of the biggest slaughterhouses in the world.

Visually it was incredible to see all this pink flesh in a very systemised infrastructure. There is this dark humour, I like about it. As someone who is very into food, there’s a very interesting debate to be had about the way we consume this kind of food. I have actually sold quite a few prints from that series in a very large size, and I get quite a kick out of thinking someone has that hanging above their fireplace – or bed.

And of course making The Art of Impossible book!

How did The Art of Impossible come about?

I remember Bang & Olufsen from my childhood – my granddad had a B&O TV – and it has always been on my radar as a really interesting company. When I moved to Denmark, I became even more aware of it – it was obviously the kind of company I would like to explore. Through a friend, I arranged a meeting with someone very senior in the company and pitched them the idea of doing this book. To my surprise they went for it all the way. I was really allowed to make the book that I wanted, with very little interference.

"There are very few images of actual products in the book, you can see them in other places - I was intested in the things you don't get to see in other places"

Alastair Philip Wiper

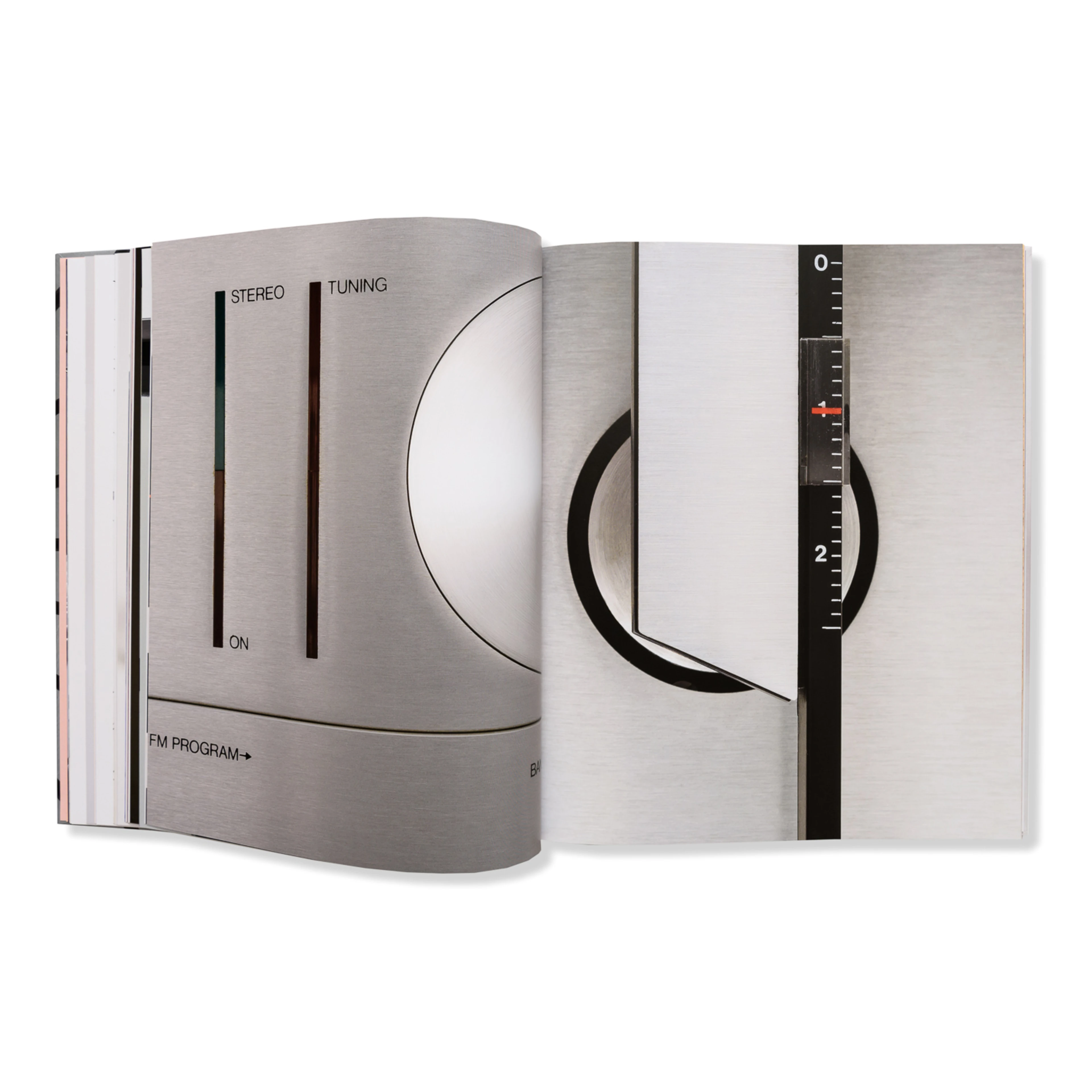

The company has so much history with so many iconic products. I wanted to show all of that but in a way, which hadn’t been seen before. Something different from the glossy marketing. We got a good publisher on board, Thames & Hudson, and I set about exploring the facilities in Struer: scouring the basements for old prototypes, walking around the factory and watching products being tested in the R&D department. There are very few images of actual products in the book, you can see those in other places. I was more interested in all the things you usually don’t get to see. I wanted it to be fun to look through and make people smile. The last thing I wanted to make was a boring design book.

What was a personal highlight of The Art of Impossible project?

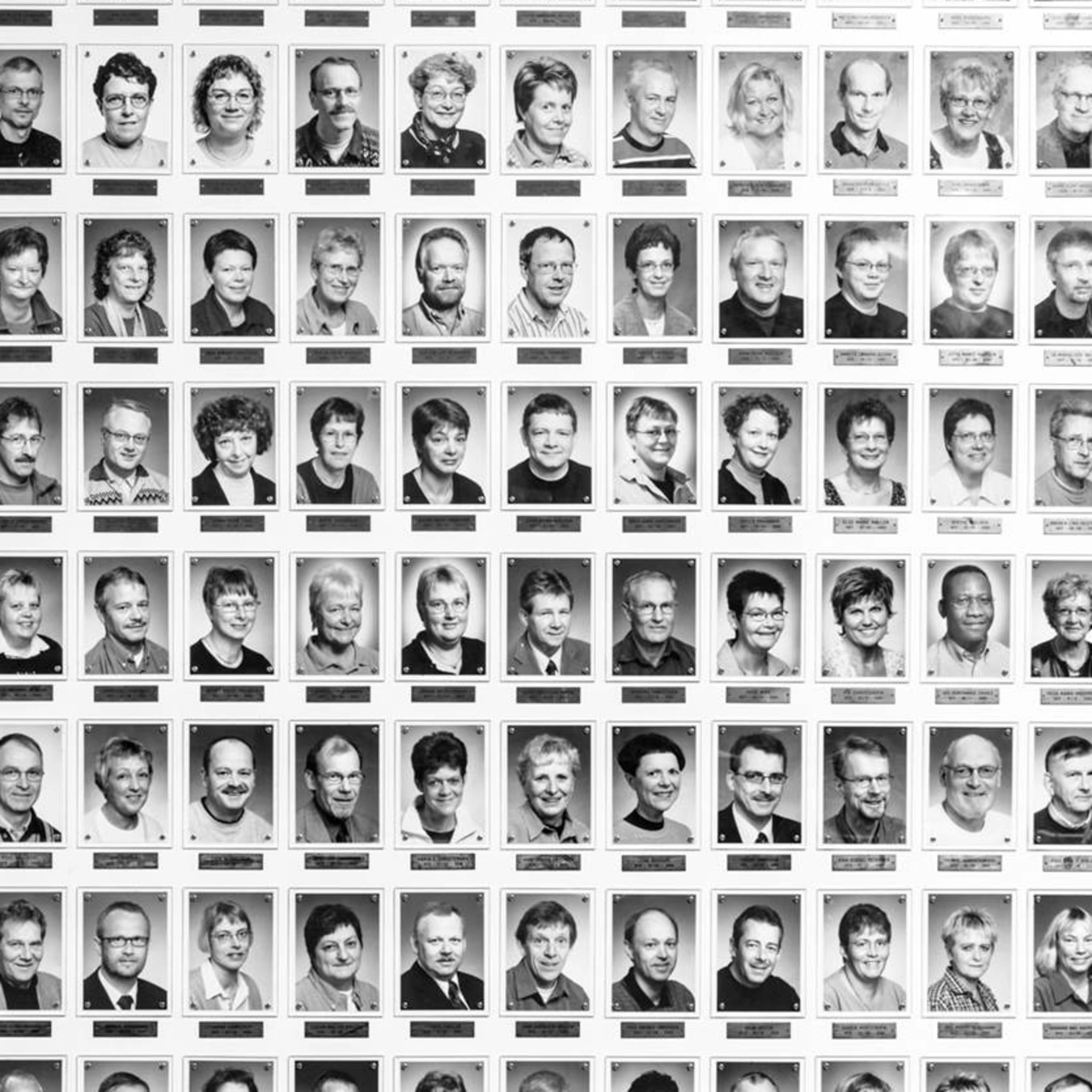

There is this 30m long wall in the canteen of Factory 4 in Struer that has the photo of everyone that has worked for B&O for more than 25 years. It’s known as the “Wall of Fame” and there are 1,231 pictures on that wall. It’s pretty awe inspiring to think there are that many people that have worked there for so long. This wall became one of the inspirations for the book.

So we reproduced the whole thing in the book, taking up 14 pages. I thought that either B&O or the publisher would think it was overkill but everyone was totally for it. There might be more “epic” images in the book, but if there is one part that really makes me smile it is that section (and seeing the style of haircuts and glasses change over 70 years is pretty fun too).

Join the House of Bang & Olufsen

Be the first to enjoy new and limited products, exclusive events, special offers and much more.